I arrived at the Bus Park at exactly 6:00am and the action was already on; touts courting passengers. One sought me out shouting, “Mbarara?” I nodded no and he continued, “Kabale?” Still no. Another guessed, “Fort Portal?” This time I responded “Kotido”. As if it was a joke, he cut in, “Soroti.”

“Kotido via Nakapiripirit,” I insisted. He took one look at me, wondering whether I knew what I was talking about. Not with the dreadlocks, headphones, jeans, boots and knapsack. Reluctantly, he took my hand and led me away. After delivering me safely to the bus stop, he said, “Okay wait here. But mama, nga you come from far!”

After 30 minutes of waiting, the bus arrived and we boarded. Almost everyone in the bus spoke English, occasionally spicing it with the local language. By eavesdropping on my neighbour’s conversation, I was able to learn a few things about the unfamiliar place I was headed for.

At 7:00am, we sped off in an almost empty bus, which eventually filled up along the way. I soon realized that my guide in Kampala had given me katwa (wrong information). First, she made me wait in the cold for a bus that leaves at 7:00am. Then she assured me that the journey was only five hours! Well, we reached Mbale, a few minutes after 11:00am, and I was sure Nakapiripirit was not just two hours away.

After 30 minutes at the bus park, we were on our way through Sironko’s smooth tarmac road, and wow! The locals really make full use of the resources. The tarmac doubles as a drying rack for grain food like maize, beans and sorghum. It’s up to the driver to avoid it.

We rolled smoothly along the neat tarmac until reality slapped us in the face in the form of two huge billboards: one indicating the branch off to Kapchorwa and the other declaring: “End of Tarmac to Moroto.” Such unfairness! The branch off also served as a reminder that Karamoja was so near.

The terrain changed from plantation of bananas, maize, etc. to long grass and shrubs. The mountain ranges continued but it was different from the rain fed Elgon slopes. The wind also blew harshly. We soon encountered our first road block, mounted by soldiers from a nearby detach. Apparently, their duty is to patrol the high way and protect travellers from the marauding Karamajong ex-warriors.

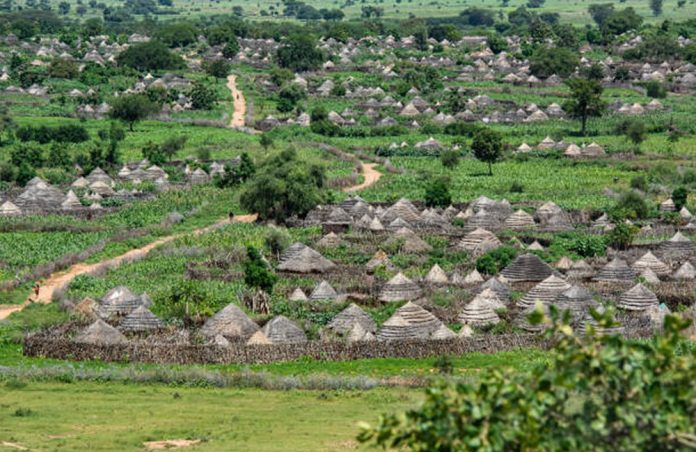

We were soon speeding through Pian Game Reserve, and past Uganda Wild Life Authority (UWA) offices. In the distance, we spotted some antelopes and ostriches standing in the long grass. The locals built their homes nest to these offices for security reasons. Their homes are fenced with wood while the gardens of greens, sorghum, and maize are fenced with thorns. The idea is to keep out stray animals such as leopards and antelopes.

Finally, we arrived in Nakapiripirit town, a few minutes past 4:00pm. The district headquarters are a stone throw away from the bus stop. I headed straight there to look for the District Information Officer. According to him, my arrival in the District was a good omen. The night before, it rained for the first time in a month.

I tried to make friends with the locals. It was a stubborn chap I met first. First, he denied having a first name claiming he was never baptised. Then, I had to milk him of his age and class which turned out to be 12 years and primary seven respectively. But first, I had to tell him my age and job. Then he opened up. For him, it’s a story for the survival for the fittest. His entire family was killed by Pokot warriors five years ago. Now, he is on his own, he sells water and runs errands for survival, and is tapping into the free education under the Universal Primary education programme. It’s him who eventually reveals to me why the Karamajong hate photographs. “Here, when your picture appears in the papers, and you are recognised, you are in trouble,” he says.

As I walked through the town, I noticed the unique dress code for the warriors. On top of their clothes, the men add a red/blue stripped suuka across the chest, plus other accessories like the Karamoja roadway sandals made out of car tyres, a stick or an illegal gun, an AM/FM radio set, a three legged wooden stool and a stick toothbrush. I later found out that they have to don this regalia if they are to command respect from their peers.

For the girls, the fashionable Ekapelo skirt has never left the scene. It is round, multi-coloured, with numerous pleats. It takes savings of shs 500-800 of milk sales every day to buy at least three skirts, each at shs 2,500. That skirt does magic as it swings and wiggles the wearer’s waist as she goes about her work.

One of my many tours took me to the municipality’s only primary school. The deputy headmaster took us through the school. I inquired about the kids who stayed home. “Here, children study at free will. You can’t force a parent to let their child come to school, not even to buy a school uniform. But we see the numbers increase at lunch time,” he said. Education is indeed voluntary here. School officially opens at 8:00am, but, by 9:00 or 10:00am, kids are taking porridge with their parents and some are seen playing by the roadside. Those who bother are carrying a log or two to school.